BBC Wales Investigates

BBC Shared Data Unit

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThousands of sites potentially contaminated with toxic chemicals in Britain have never been checked by councils, a BBC investigation has found.

Nine out of 10 “high-risk” areas have not been tested by councils responding to a BBC Freedom of Information request and scientists fear they could pose a health risk as they are thought to contain substances such as lead or arsenic.

The BBC Shared Data Unit found of 13,093 potentially toxic sites that councils have identified as high risk, only 1,465 have been inspected.

The UK government said local unitary authorities had a statutory duty to inspect potentially contaminated sites but councils claim they do not have the money to do it.

The Environmental Protection Act requires councils to list all potential contaminated sites, and inspect the high-risk ones to make sure people and property are not at risk.

But after contacting all 122 unitary authorities in Wales, Scotland and England about their contaminated land, 73 responded to the BBC’s Shared Data Unit Freedom of Information request which revealed there were 430,000 potential sites identified in the early 2000s.

Of those, 13,093 were considered to be potentially high risk, which experts said should have then been subject to physical testing. Yet, more than 11,000 of them remain unchecked to this day.

Half of Wales’ 22 councils told the BBC they could not or would not give us figures – but those that did, identified 698 high-risk sites of which 586 have not been inspected.

The research comes after the release of new Netflix drama Toxic Town which tells the story of families fighting for justice following one of the UK’s biggest environmental scandals.

The BBC’s findings raise fresh questions about what exactly has been left beneath our feet from the UK’s heavy industrial past.

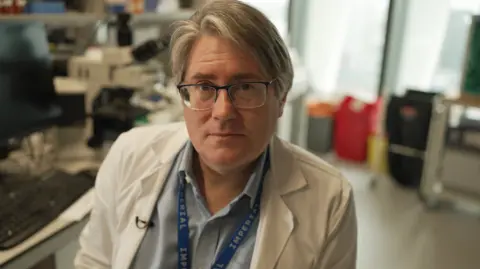

“What we don’t do in this country is do a full economic evaluation on the cost of things, including health and that feels almost criminal,” said Dr Ian Mudway, a leading expert on the effect of pollution on human health.

“I’m not even certain we’ve achieved the point of scratching the surface.”

Contaminated land is a site that might have been polluted from its previous use – it could have been a factory, power station, a railway line, landfill site, petrol station or dry cleaners.

If you live in a property constructed after 2000, any contamination issues should be covered by updated planning laws.

But if you live in a property built before 2000, the rules are less clear.

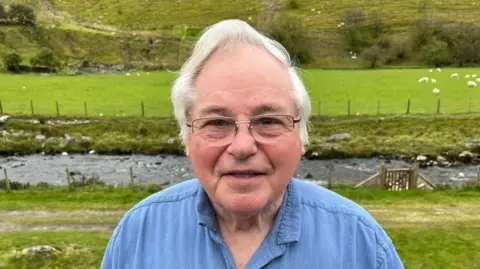

Where Robin Morris lives is home to more than 400 of Wales’ 1,300 abandoned metal mines and its three rivers, the Ystwyth, Rheidol and the Clarach, are some of the most heavily-polluted in the UK.

The Cwmystwyth mines in north Ceredigion date back to the Bronze Age and were abandoned in 1950, but spoils including a high level of zinc, cadmium and lead scatter the landscape and have polluted the River Ystwyth below.

Many Cwmystwyth locals, like Robin, have filtration systems installed if they receive their water from the hills where the old mines were.

“We installed an advance filtration system and were assured it would take absolutely everything,” he said.

‘Alarm bells’

The BBC took a soil sample from Robin’s garden on the banks of the Ystwyth and it revealed a very high reading of lead – well above the recommended safe level for gardening.

“It causes alarm bells to ring,” Robin told BBC Wales Investigates.

“In light of the figures from your soil sample, we should have stopped growing vegetables long ago.”

It’s just one sample, but other things that have happened in the past now seem to make more sense.

“We had ducks and chickens, a couple of the ducks went lame and we did consult the vet, he thought it was because of lead contamination,” added Robin.

Ceredigion council said it was liaising with Wales’ environmental body National Resources Wales to continually assess the health impact from the area’s mining legacy.

Dr Mudway insists there was “no safe level” of lead and told the BBC it could impact children’s development as well as kidney and cardiovascular disease in adults.

“Nothing is more of a forever chemical than lead,” added the environmental toxicologist at Imperial College London.

“This is a hazard that has not gone away and is still a clear and present danger to the population.

“It’s one of the few chemical entities for which we can calculate a global burden of disease – between half a million to just under a million premature deaths per year because of the release of lead into our environment.

“When you talk about the cost of ensuring that land is safe… that costs money up front.

“The costs of potential health effects, especially if they contribute to chronic diseases which people live with for 10 or 20 years, or the costs of remediating land, after when you realise that it’s a high-level, dwarf the profits made at the other end of that cycle. That feels almost criminal.

“The health cost is hardly considered at all.”

Huw Chiswell

Huw ChiswellWhen Manon Chiswell was a toddler she suddenly stopped talking – doctors advised her family she was showing lots of autistic traits.

“I do have memories of being very closely monitored in Meithrin [nursery]… I always had an adult with me,” said Manon, now 20.

“I couldn’t speak… they had to use a traffic light system, and yes or no cards to redirect me and help me communicate.”

But a blood test later found high levels of lead in Manon’s blood.

She was not autistic, she had been poisoned.

Her father, Huw Chiswell, believed Manon was most likely poisoned at their home in Cardiff, which was near an old industrial site.

“She used to eat earth [as a toddler] in the garden,” he said.

“There were railway sidings not far from where we lived at the time, so it’s difficult to draw any other conclusions really, because once she’d stopped the eating, she got better.”

But it is not just about lead – a government report suggests that sites posing the greatest health risks were also contaminated by chemicals such as arsenic, nickel, chromium, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) found in soil or water.

PA Media

PA MediaCampaigners want a new law forcing councils to keep a public register of all potential contaminated sites.

It is led by the parents of a seven-year-old boy who died from poisonous gas after the River Thames flooded their home in 2014, and they believe the fumes came from a nearby landfill.

Zane’s law – named after Zane Gbangbola – also calls for measures such as more money for councils to identify and test possible sites.

“You have to know that it exists before you can protect yourself,” said Zane’s dad Kye Gbangbola, who was left paralysed after the gas poisoning.

“Until we have Zane’s Law people will remain unprotected.”

When tighter regulations on dealing with potentially contaminated land became law 25 years ago, the minister that pushed them through wanted just that.

Now John Selwyn Gummer feels UK government funding cuts has meant far fewer inspections.

“There is no way in which local authorities can do this job without having the resources,” said Lord Deben.

“Successive governments have under-provided for the work that we need to do.”

‘There’s a possibility some people’s health is being threatened’

Several councils have told the BBC that funding is the reason they had stopped checking possible contaminated land.

Phil Hartley was one of hundreds of officers across the UK that used to check potential sites as Newcastle’s former council contamination officer.

He said the central government grant removal had led to a “collapse” in checks.

“Since the money dried up very, very few councils proactively go out looking for contaminated land sites because the council doesn’t want to take the risk of finding them,” said Mr Hartley.

“There’s a possibility that some people’s health is being threatened, which is not great.”

The UK government said local authorities had a statutory duty to inspect potentially contaminated sites, require remediation and maintain a public register of remediated land.

“Any risk to public health from contaminated land is a serious matter,” a spokesperson from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said.

They also asked the Environment Agency to produce a new state of contaminated land report to provide the “best possible baseline of data to measure future policies related to contaminated land against”.

The bodies that represent councils in Wales and England both said a lack of cash meant they could not fulfil their duty.

The Welsh Local Government Association said while Wales’ 22 councils took their responsibility to check sites “seriously”, progress was “increasingly constrained by a lack of dedicated funding and specialist resources”.

England’s Local Government Association said: “Without adequate funding, councils will continue to struggle to provide crucial services – with devastating consequences for those who rely on them.”

You can watch Britain’s Toxic Secret on BBC iPlayer and BBC One on Thursday 13 March at 20:30 GMT